Richard Dawkins. The God Delusion. Harrumph.

Dawkins is aggravated at magical precepts and objects of belief. Moreover, as many are, he finds the religious game of king of the hill destructive. But, Dawkins is somehow prevented by the mote in his eye from realizing that faith, belief, are completely normal features of the consciousness the most sentient of creatures use to navigate a world not configured to yield ‘scientific’ results in each and every case.

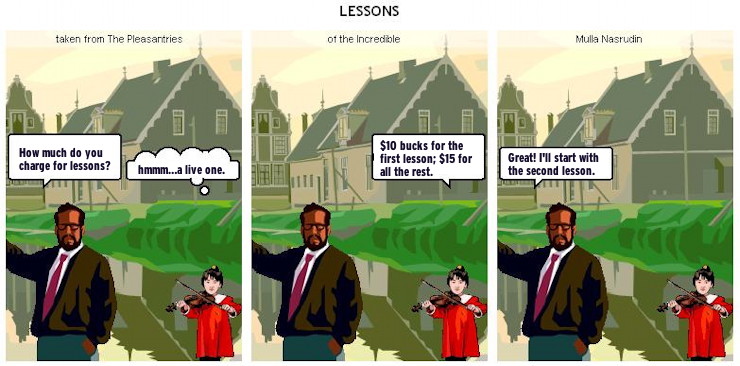

Were we to break down our choicemaking day in and day out and drill into our cognitive complexity, into our consciousness, we’d soon, immediately discover, that the terms of our navigation are largely funded by belief. And faith. In dumb little stuff. We believe we’ve picked the best tomato from the pile. We’re pragmatists and the core proposition underlying the utility of almost all our sundry suppositions is that we believe that they are true.

This is lost on Dawkins. In a post to follow I’ll tell of my several encounters with free thinkers, methodological materialists, and various “Brights”. Every single one is united by their shared discomfort with psychologizing and psychology. And, they’re united by their unreasonable faith that their findings per force apply to moi because “it is just so”.

Terry Eagleton. Lunging, Flailing, Mispunching (London Review of Books; Oct.19, 2006)

Dawkins’s Supreme Being is the God of those who seek to avert divine wrath by sacrificing animals, being choosy in their diet and being impeccably well behaved. They cannot accept the scandal that God loves them just as they are, in all their moral shabbiness. This is one reason St Paul remarks that the law is cursed. Dawkins sees Christianity in terms of a narrowly legalistic notion of atonement – of a brutally vindictive God sacrificing his own child in recompense for being offended – and describes the belief as vicious and obnoxious. It’s a safe bet that the Archbishop of Canterbury couldn’t agree more. It was the imperial Roman state, not God, that murdered Jesus.

Gary Wolf. The Church of the Non-Believers (Wired Magazine; Nov. 14, 2006)

The New Atheists have castigated fundamentalism and branded even the mildest religious liberals as enablers of a vengeful mob. Everybody who does not join them is an ally of the Taliban. But, so far, their provocation has failed to take hold. Given all the religious trauma in the world, I take this as good news. Even those of us who sympathize intellectually have good reasons to wish that the New Atheists continue to seem absurd. If we reject their polemics, if we continue to have respectful conversations even about things we find ridiculous, this doesn’t necessarily mean we’ve lost our convictions or our sanity. It simply reflects our deepest, democratic values. Or, you might say, our bedrock faith: the faith that no matter how confident we are in our beliefs, there’s always a chance we could turn out to be wrong.

Of course, as artifice, considered from the grids of sociology and anthropology, (thus: as history,) religion, and various human instantiations of vast systems for principled organizing are interesting far beyond their arrayed assumptions. Utility, again…

Thomas Nagel. The Fear of Religion (The New Republic; Oct. 23, 2006; avail. EBSCO)

I also think that there is no reason to undertake the project in the first place. We have more than one form of understanding. Different forms of understanding are needed for different kinds of subject matter. The great achievements of physical science do not make it capable of encompassing everything, from mathematics to ethics to the experiences of a living animal. We have no reason to dismiss moral reasoning, introspection, or conceptual analysis as ways of discovering the truth just because they are not physics.

Any anti-reductionist view leaves us with very serious problems about how the mutually irreducible types of truths about the world are related. At least part of the truth about us is that we are physical organisms composed of ordinary chemical elements. If thinking, feeling, and valuing aren’t merely complicated physical states of the organism, what are they? What is their relation to the brain processes on which they seem to depend? More: if evolution is a purely physical causal process, how can it have brought into existence conscious beings?

A religious worldview is only one response to the conviction that the physical description of the world is incomplete. Dawkins says with some justice that the will of God provides a too easy explanation of anything we cannot otherwise understand, and therefore brings inquiry to a stop. Religion need not have this effect, but it can. It would be more reasonable, in my estimation, to admit that we do not now have the understanding or the knowledge on which to base a comprehensive theory of reality.

Dawkins seems to believe that if people could be persuaded to give up the God Hypothesis on scientific grounds, the world would be a better place– not just intellectually, but also morally and politically. He is horrified–as who cannot be?–by the dreadful things that continue to be done in the name of religion, and he argues that the sort of religious conviction that includes a built-in resistance to reason is the true motive behind many of them. But there is no connection between the fascinating philosophical and scientific questions posed by the argument from design and the attacks of September 11. Blind faith and the authority of dogma are dangerous; the view that we can make ultimate sense of the world only by understanding it as the expression of mind or purpose is not. It is unreasonable to think that one must refute the second in order to resist the first.

When anybody assumes that their universal theism or scientism applies to me–too–and offers as proof, “it is just so,” then I might be inclined to point out the obvious problem of presumption. On the other hand, it’s amazing to me, to this day, that many sophisticated believers haven’t given any thought to the ramifications of their universalizing beliefs.

This is aside from how unsympathetic I personally am to magical belief systems, chains of being, anthropomorphic or deistic personification, and, especially, to the concept of a godly ‘dude’ who sits at some holy control panel messing with human affairs. But, each to their own even if many can’t grok the deal via which god doesn’t mess with me and I don’t mess with god.

Incidentally, after thirty years of meditation and contemplation, it’s enough to reveal out of my own spiritual affair, that my hope for myself is that my prejudices, when deployed consciously, disrupt any propensity to do harm. As for my beliefs, I echo John Lilly, “my beliefs are unbelievable!”.