(source: Zen Forest Sayings of the Master, complied by Soiku Shigematsu)

Monthly Archives: November 2010

Brief, Not Very Olsonian Reflections: The Prize

On Saturday I was chosen to cap a conference, Soul In Buffalo; A three-day free conference aimed to celebrate and explore Charles Olson’s legacy and extension through A Curriculum of the Soul.

This honored closing position expressed a counter-intuitive programming choice, because I am not an Olsonian. Yet, obviously, since I wasn’t going to weigh in at the end with poetry, poetics, research, or scholarly fireworks, I was, nevertheless, given the opportunity to bring some other set of capabilities to bear on the proceedings.

What I could do and what I did sort of manage to do is bring the conference to a close on wings of experience and play and collaborative grappling with a very simple creative problem. Taking this creative problem first, I asked the group to participate in a squareONE tool, Hunting and Gathering, and use it to bring several explicit things into greater focus, and, as well, bring whatever the process might evoke into their collaborative field of experiential play and creativity.

I will tender the explicit things momentarily. What might of happened references what is my usual way of facilitating Hunting and Gathering. This usually happens within a slice of time able to support my gentle guidance of an experiential process to its important goals. Those goals exist on a continuum stretched on one end between learning with enough gravity to support testing or further experimentation, and, on the other end, learning which is galvanizing to the point of an a-ha.

Yet, this time out the time slice ended up being compressed to about an hour. As Idries Shah once put it, “time takes time.” So, with this lessened time I quickly had to make a few strategic decisions. This has happened on a few occasions in the past, but I have never intentionally turned a finely tuned process into a grand experiment–as I ended up doing on Saturday.

I framed, (or ‘primed,’) the group’s experience by introducing several factors, in the form of musings. I told the group I wasn’t an Olsonian, but had come to this conference by virtue of remarkable serendipities having to do with encounters with friends-who-were Olsonians. Then I very briefly pointed out that soul might have something to do with creating together via relationships, and using as its raw stuff the discoveries found in exploration. I hoped the experience I was offering would drive some into the experience of soul in real-time. And, my personalization brought up what seem to me an essential feature of soulful working together: its human contingencies are fragile, and yet, are loving too.

(I recognize here my prejudice too: deep soul is very human, rather than very esoteric!)

The sharpest suggestion I made was this: whatever learning comes to happen may be referenced in his or her reflection on a personal intention I had them generate. However, in my strategic alteration of the process I understood going in to it, I would never learn anything about their learning.

What unfolded was pretty damn amazing, even by my experienced standards. I do not debrief my work for all the world to read and see, but it is enough to tell of a quickening vibration that rose like heat waves off a desert.

I had split the group into two sections and both worked on their collaborative graphic. The differentiation of approach, as I felt it and as I mused over the ‘consequence of approach,’ was very telling about challenges not much spoken of in the two days of stunning contributions I witnessed. The general challenge is about how various bodies of work come to persist, be sustained, grow, and, in the soulful turn, come to have positive effects on the growth of consciousness as this is individually rendered in the alchemical cooker of devoted, unsparing, deeply humanized, relationship.

oiled snake

psychedelic reverb

straight no chaser

spot your choices

still have to live

alive among

each other

Filed under adult learning, creative captures, Kenneth Warren

Reduced Bateson Set II. Set up; Participant-Dependence

Consider a thought problem about human whistling.

You are placed in the role of observer. Presented to you is a person who will whistle Mary Had A Little Lamb. Your direction for the exercise is to describe the act of this person whistling this tune. The only qualification for the description you are to document is that you are able to articulate for any of its elements what each has to do with the whistling you are observing.

At the conclusion of you, the observer, documenting observations, your report will be evaluated against two constructs: Observer-Independence/Observer-Dependence. Each element of observation will be classified as being one, or the other.

For the purpose of the former classification, Observer-Independent descriptive elements are those elements that are necessary to human whistling, and, do not require prior knowledge beyond the modest scope given by self-observation.

For example, to state:

(1) I am observing a whistler.

(2) Whistler whistling have to include a human with a blood-pumping heart.

(3) Whistling has to include brain activity.

is to assert Observer-Independent elements.

For example, to state:

(1) This is a fast version of the tune.

(2) The whistling is loud.

(3) The last passage was uncertainly in-tune.

is to assert Observer-Dependent elements. These latter descriptions are not necessarily findings every observers could possibly note.

The situation given by observations rendered through using particular kinds of prior knowledge have feet in both camps. A physiologist might identify a muscle necessary to whistling. The muscle is used in every instance of whistling. Yet, this prior knowledge is instituted only by the kind of observer who can employ it.

What we have here, in such a thought problem–and it’s one which could be done–is one human system observing the acts of another human system. The observations could be furthered qualified with respect to what is their subjective quotient.

There’s a paradox in all this. Let’s say the problem to be solved is this: predict the time the tune will be finished. What kind of information derived from prior observations of other whistlers would be helpful in deciding the answer? Interestingly, much of the Observer-Independent information about the human whistler is completely useless. Even if we formalize this to include specialized (in some formal sense) prior knowledge, most of that kind of information will be useless with respect to simple problems, and the simple problems out of which more complex problem are built.

Would you be able to detail the features of, for example, the heuristic you commonly employ for the sake of getting to know another person? Many dyadic, and group, procedures for inquiry are born by meshing of ‘heuristical’ tools, given differently to such procedures by the various (so-to-speak) parties. Another paradox is that these meshed procedures may be, often are, very effective means for making an inquiry, even though the underlying heuristics are not roughly the same, or similar, or commensurate with one another. In fact, parties to inquiry may not have thought through the very tools he or she employs. These tools can be said to be partly tacit to the user: they operate without the operator entirely knowing what is being operated by their self.

The formal means for understanding complex interactive inquiries use prior knowledge and formalized methods, yet these means are not precisely useful when trained on everyday–for example–interpersonal actualities. If these means can’t unravel whistling, they won’t be more powerful with many times more complex phenomena.

Yet, this situation, the basic imprecision of both informal and formal naturalistic inquiry when trained on particularized subjects, is extended to almost every natural process where knowledge is presented in particularized subjects and situations. So: a marketing idea is presented; a developmental plan is presented; an interpretation is offered; a self-report is revealed; an illustrative story is told; etc., and each of these exchanges is about something truthful, and, each is also about that which constitutes the human system, so-to-speak, of presenting its stuff, and its moment of some kind of truth.

The Reduced Bateson Set, appropriated from my interpretation of Bateson, collects six motifs, (Bateson’s term,) in an array of three positions and three orders. This array of motifs sets up the following means for interpreting a ‘presentation.’

It locates the human subject. It suggests by way of interpretation and analysis that explicit choices reveal implicit choices, and, reveal what is not chosen. It does the same for figuring out what is and is not connected to positive actuality. Then, along the other ‘side’ of the array, it qualifies these motific means with respect to how sensitive the human subject is to modifying their presentation. This latter means for interpretation and analysis holds that this sensitivity itself refers to implicit choices which argue for the human system being, roughly, flexible or not flexible.

Roughly, the suggestion is this: there are human exchanges of knowledge, and these are most often, or commonly, ‘heuristical’ on the part of both parties. What is then given by this flux of two largely informal systems are informal understandings. Embedded in such understandings are great amounts of implicit and tacit givens; threaded into this also are other systems; partialities of informal and formal prior knowledge; histories of experience; and, among many other factors, novelties and innovations given by the specific consequences granted in two or more particular human systems coming into particular participation together over the matter of an exchange of knowledge; alternately, information.

The flux in this human system is a situation of Participation-dependence, which is to say the practical description of the seeming paradox is that there are, for example discussions between two people that necessarily instantiate such an exchange, yet, in this, often widely disparate, individualized features in direct relation to the matter of exchange are not also relevant factors in the exchange. In other words, to turn the Batesonian cybernetic posit on its head, in these instances–which are everyday and ubiquitous, some differences do not make any difference.

My suggestion here is this kind of smoothing of difference allows two people, two human systems of awareness, to conduct exchanges of information without introducing what are demonstrably pertinent differences discoverable as features not shared between the two people.

Another way to put it, is that a conversation proceeds productively without negotiation of, for example, pertinent unshared assumptions.

Were we to convene a group mixed between technical experts and keen observers who are not technical experts, the answer to the question, ‘when will the whistler stop whistling?’ will not arise as a matter of differentiating between formal or informal estimates. However, this same group can productively discuss this question and do so without entertaining its individualized and specific to each member, assumptions about how to answer the question.

Any number of similar thought problems can be created. In each such problem, the suggestion is that there are a large, if not infinite, number of questions which can be discussed but not resolved by the efficacy of either formal or heuristic prior knowledge.

There are two currents given here. One is that the discussion can nevertheless evoke knowledge, and, that the discussion cannot evoke knowledge-in-the-form of an accurate prediction.

From here I would next move to support the claim that most exchanges of knowledge in everyday circumstances refers to heuristical means, is constructed from individualized heuristics, and that the differentiation of this heuristic basis does not prevent productive and efficacious exchanges.

The differences are smoothed over so that these exchanges may happen.

Filed under Gregory Bateson

Soul In Buffalo November 18, 19, 20

A three-day free conference will celebrate and explore Charles Olson’s legacy and extension through A Curriculum of the Soul, a series of poetic essays published as fascicles by Albert Glover and John C. (Jack) Clarke.

Riffs, Research and ResistanceWith Albert Glover, Daniel Zimmerman, Michael Bylebyl, David Tirrell, Michael Boughn, B. Cass Clarke, Victor Coleman, Steve McCaffery, Stephen Baraban, John Roche, Andre Spears, Joen Napora, Stephen Ellis, Alan Casline and Kenneth Warren.

Nov. 18 11 a.m. – 4 p.m. Poetry Room at UB, 420 Capen Hall

Nov. 19 & 20 11 a.m. – 4 p.m. Karpeles Manuscript Museum, 453 Porter Ave.

squareONE toolmakers, as in yours truly, will be providing the tool Hunting and Gathering and using it to go playing with gods–in an experiential playing, and digging, and reaching, for soul; as the last event on Saturday. (See below)

Schedule – Soul In Buffalo

Thursday November 18 – Poetry Room at UB – 420 Capen Hall

11 – 11:40 A CURRICULUM OF THE SOUL: AN INTRODUCTION – Albert Glover

11:40 – 12:00 A CURRICULUM OF THE SOUL: AN ACCOUNT – B. Cass Clarke

12:00 – 12:45 THE COST BENEFIT RATIO: AN INQUIRY – Albert Glover,

Pat Glover, and B. Cass Clarke. Moderated by Alan Casline12:45 – 1 Break

1 – 1:20 WHAT IS A SOUL AND WHY MIGHT IT NEED A CURRICULUM – Michael Boughn

1:20 – 2:00 IN THE OFFING – Daniel Zimmerman

2:00 – 2:40 PERSON AND TEXT: A CONVERSATION – Michael Boughn, Daniel

Zimmerman, Michael Bylebyl and Victor Colman. Moderated by John Roche.3:00 – 3:10 POETRY IN FATHAR – David Tirrell

3:10 – 4:00 READING FROM A CURRICULUM OF THE SOUL – Albert Glover,

Daniel Zimmerman, Michael Bylebyl, David Tirrell, Michael BoughnFriday November 19 – Karpeles Manuscript Museum – 453 Porter Avenue

11 – 11:30 THE MUSHROOM – Albert Glover

11:30 -12 ROOTDRINKER RESONANCE – Alan Casline

12 – 12:30 – JACK CLARKE”S HOMEWORK – Charles Palau

12:30 – 1:00 WRITING THE CUR(S)E: THE MISSING PROJECT IN PROJECTIVE

VERSE – Joe Napora1:00 – 1:30 Break

1:30 – 2:00 BRITISH SOUL AND ITS CURRICULUM(S): NOTES ON OLSON AT

KENT – André Spears2:00 – 2:30 A CURRICULUM OF THE SOUL: JOHN THORPE – Stephen Ellis

2:30 – 3:00 NATURE AS SCRIPT – John Martone

3 – 3:30 OLSON, MAYAN, ETHNOPOETICS, LANGUAGE SYSTEMS AND SAINT

AUGUSTINE – Steve McCaffery3:30 – 4:00 OPEN SPACE DISCUSSION – Steve Tills

Saturday November 20 – Karpeles Manuscript Museum – 453 Porter Avenue

11 – 11:30 WHAT’S UP IN A NUMBER, 23 SKIDOO, AND GERRIT LANSING’S

ANALYTIC PSYCHOLOGY – Robert Podgurski11:30 -12:00 BETWEEN LANGUAGE AND TA’WIL: ROBERT CREELEY, JACK CLARKE

AND POETICS IN BUFFALO AFTER OLSON – Kenneth Warren12:00 – 12:30 JACK BE NIMBLE: ON JACK CLARKE’S GLOUCESTER TRANSLATIONS

– Stephen Baraban12:30 – 1:00 DUNCAN AND JOEL, THE ECOLOGY OF THE SOUL – David Landrey

1:00 -1:30 Break

1:30 – 2:00 ONE HERO: APOLLONIUS OF TYANA – IMPLICATIONS FOR THE

SOUL: A CONVERSATION – Kitty Jospé2:00 – 3:30 PLAYING WITH THE GODS: A MOMENT FOR EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING

IN A CURRICULUM OF THE SOUL – Stephen Calhoun3:30 – 4:00 OPEN SPACE MUSIC WRAP-UP – Kevin Doyle

Filed under adult learning, Kenneth Warren

Treating the Game As A Game

One of the conventions the Free Play handicapper implements is to set one elder against the other. Here the elders embrace after the contest, and you can’t tell who was on what side of a 20-4 score, can you?

F(ather): Suppose you tell me what you would understand by the words “serious” and a “game.”

D(aughter): Well… if you’re… I don’t know.

F: If I am what?

D: I mean… the conversations are serious for me, but if you are only playing a

game…

F: Steady now. Let’s look at what is good and what is bad about “playing” and

“games.” First of all, I don’t mind —not much—about winning or losing. When your questions put me in a tight spot, sure, I try a little harder to think straight and to say clearly what I mean. But I don’t bluff and I don’t set traps. There is no temptation to cheat.

D: That’s just it. It’s not serious to you. It’s a game. People who cheat just don’t know how to play. They treat a game as though it were serious.

F:But it is serious.

D: No, it isn’t—not for you it isn’t.

F: Because I don’t even want to cheat?

D: Yes—partly that.

F: But do you want to cheat and bluff all the time?

D: No—of course not.

F: Well then?

D: Oh—Daddy—you’ll never understand.

F: I guess I never will.

F: Look, I scored a sort of debating point just now by forcing you to admit that you

don’t want to cheat—and then I tied onto that admission the conclusion that therefore the conversations are not “serious” for you either. Was that a sort of cheating?

D: Yes—sort of.

F: I agree—I think it was. I’m sorry.

D: You see, Daddy—if I cheated or wanted to cheat, that would mean that I was not

serious about the things we talk about. It would mean that I was only playing a

game with you.

F: Yes, that makes sense.

(excerpt; 2.3 Metalogue: About Games and Being Serious | Steps to An Ecology of the Mind; Gregory Bateson)

Filed under Gregory Bateson

Snowy Daze

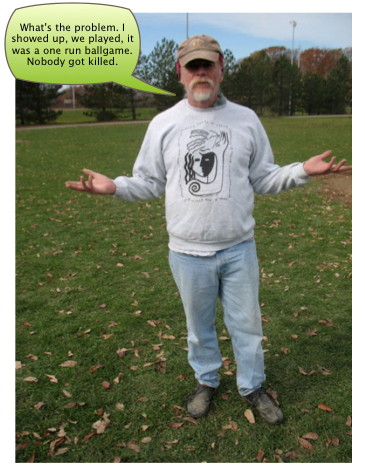

A pic taken after our October 31, Free Play Softball League game. It was quite a game, another one run affair, and capped off by a game winning hit that fell in a grey area. What’s a grey area on a softball field. Well, it’s about three feet to the foul side of a foul line marker (1), but also in the fair territory as defined by a straight line drawn through the points of home plate and third base. I was the left fielder who deferred from making a total heroic effort on a catch-able ball. I couldn’t believe what happened and trotted in and was obnoxious for a brief moment. Yet, as the winning team’s wave of positive affect rolled over me, I submitted to the Free Play game’s Hermes.

The next week, on November 7, was another unique, and, one run game, ended by a monster base-clearing strike by Kurt. Here he is putting bats away.

Because I usually am holding the camera, I’m not in most team shots. Frances, thinking of my fragile ego no doubt, asked for the camera, took this shot, and told me to put a caption to it. Which I have.

Let me explain: at 10:05, five minutes after the game usually starts, my cell phone rings. I’m absorbed twiddling knobs in the studio and begin to ignore it, when, suddenly I realize something.

It may be snowy eight miles south of Forest Hills Park, but, kid, your mates have arrived at the non-snowy field ready to play, while you’re sitting at home with your car–full of the entire inventory of essential equipment–sitting in your driveway.

(1) One perk to riding the equipment camel is I sometimes get to layout the foul markers.

Filed under adult learning

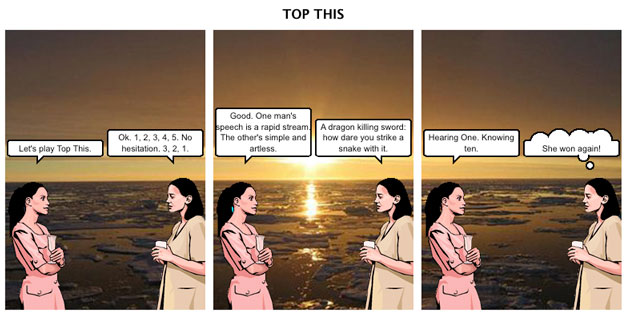

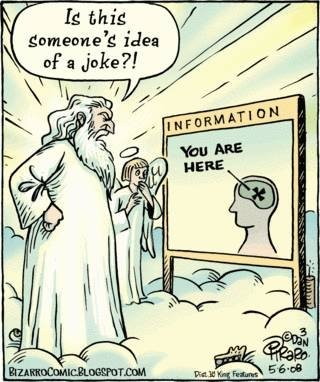

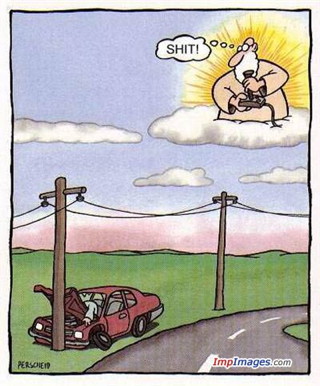

Teaching Cartoons: Two Gods

…would have been better without a caption.

I don’t know for sure, but this could represent an element of the most widespread sense of God.

Filed under experiential learning

Reduced Bateson Set I. Set Up; Meta-heuristics

Sometime ago, yet late in my scatter shot intellectual development, I realized five problems fascinated me in psychology. One is the problem of how our brain instantiates and substantiates consciousness. Two is how it came to be that the equivalent of a William James doesn’t arrive much earlier so as to shift proto-psychology forward at an earlier stage in history. This problem wonders about the relationship between culture and contemporaneous psychological categories. The third problem, related to the second problem, is coded (for me) as the problem of introspection. The fourth problem is coded too, as the bundle of problems given by folk psychology at the level of meta-psychology; ie. philosophy of psychology.

And, finally, the fifth problem, very much related to the fourth problem, is the problem of: everyday behavior joined with how psychology’s different disciplines approach everyday behavior as its object of research. I am especially intrigued by how behaviors are named despite those same names being unnecessary to persons behaving in the way the name denotes.

I will seek to explain what I call The Reduced Bateson Set in a series of posts. The Reduced Bateson Set names a framework I utilize. Meanwhile, from an authoritative source:

For the moment, the set-up for this was evoked by my trying to figure out how to describe what is The Reduced Bateson Set. I was moved to look up the definition of heuristic–or rather a definition–in a standard reference book, because I thought this might be the best descriptive term. If so, I could simply say The Reduced Bateson Set is a heuristic I have come to use and favor.

I didn’t think the term was strikingly adequate, inasmuch as I had a deviant definition of heuristic in mind.

According to the now prevailing definition, heuristics are rather parsimonious and effortless, but often fallible and logically inadequate, ways of problem solving and information processing. A heuristic provides a simplifying routine or “rule of thumb” that leads to approximate solutions to many everyday problems. However, since the heuristic does not reflect a deeper understanding of the problem structure, it may lead to serious fallacies and shortcomings under certain conditions. Thus, in contrast to the positive connotations of the original term, the modern notion of cognitive heuristics has attained the negative quality of a mental shortcut that frees the individual of the necessity to process information completely and systematically. Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Psychology

Okay, my definition turns out to be a bit too innovative! But at least it doesn’t imply a ridiculous optimal “problem solving.”

More precisely to the point here, is how rapidly I landed in a Batesonian moment. Unfolded in the encyclopedia entry is a long treatment of the term, yet, it’s not describing much about what I wish to also describe. And, the problem could be that it could not describe even what it seeks to describe–in a deep sense able to capture something very very common.

What is this something? It is that some large portion, possibly a majority portion, of human behavior is “heuristical.” Which is to suggest: it is likely a majority of human problem solving, leaarning, discovery, etc., everyday, (every darn day,) processes information incompletely and not systematically. Also, a corollary to this is: some large portion of human problem solving cannot access both a totality of pertinent information, or, have been the subject of a complete processing within, I suppose, a formal requirement for complete and systematic processing.

Wikipedia’s entry is not robust, but it is more satisfying.

Heuristic (pronounced /hj??r?st?k/) or heuristics (from the Greek “???????” for “find” or “discover”) refers to experience-based techniques for problem solving, learning, and discovery. Heuristic methods are used to come to an optimal solution as rapidly as possible. Part of this method is using a “rule of thumb”, an educated guess, an intuitive judgment, or common sense. A heuristic is a general way of solving a problem.

Except I will quarrel with it too. I don’t know the correct term for that which is a precise and focused heuristic way of solving particular everyday problems. Yet, I do understand the ‘human everyday’ presents a series of opportunities to problem solve, learn, and discover. Figuring out what you’re going wear is a particular problem, and a problem I’d suppose is solved in precise and focused ways.

(Perhaps a differentiation made among general, and, ‘problem-particular,’ methods is unnecessary.)

Among, (what I will term Batesonian,) distinctions found in definitions is this hot one. First, to develop a correct definition is itself a problem to be solved. Could it be demonstrated that any given normative (or authoritative) definition was created, subject to heuristics? Here of course I’m speaking of an example, the definition of heuristic. A second Batesonian distinction is implicit in speaking of the possible heuristics behind the term heuristic.

Here’s a doable experiment. Collect five of the foremost social psychologists together and have them each write out their definition of the term, heuristic. Assume there is a sound method for scoring to what degree the five definitions match up. For my argument here, let’s assume the result of this experiment shows a very high degree of matching.

The five world class experts are then asked to do the following: “How do you know your definition is the correct definition?” Score the answer.

Let’s do this same experiment and add the following parameter. Before either primary question is addressed, each group member is asked the following: “How many pages will you need to answer the question, How do you define heuristic?” Allow no limit in length for their written answers.

Hypotheses are to be entertained. I won’t offer these, yet I will suppose the results of this experiment will

demonstrate considerable disagreement on question number two, How do you know your definition is the correct definition, and this disagreement increases the longer any answer is to either question. So, the most disagreement would be found between the longest answers.

There’s a problem incurred by my supposing the answers could be scored. How would we score different points of emphasis? Those points could not be scored as only disagreements. Still, our scoring would have to resolve this problem in reckoning with matching points of emphasis and divergent points of emphasis.

My hunch that there would be found disagreement is, obviously, completely a matter of a decidedly intuitive and heuristic approach to thinking about the problem of defining a normative term. What I’m thinking about here is the human system able to develop useful definitions about its own features. The experiment might well defeat my hunch. But, what if the experiment proved the underlying hypotheses?

What then could be suggested by the results of this experiment about hypothesized deviations from agreement? What also could be suggested about how the problem of expert definition is approached by experts? Do these experts employ heuristics as an effective, or not effective, means?

Consider a countervailing–with respect to my hunch–supposition. That: in a description, where detail increases, deviations are reduced. (Speaking of building houses: we can all agree on the sharp nail and the straight board.) This suggests that as descriptions penetrate ‘down’ to more elemental levels of order in a system, deviations between descriptions are reduced.

My hunch asserts the opposite is possibly the experimental result. So: as experts expert in the same system propose descriptions of this system, as the level of detail increases in their descriptions, their descriptions will tend to diverge.

Again, a countervailing supposition might be rooted in the same idea given in the Blackwell encyclopedia: to define a system correctly, and so free the definition from any reliance on heuristic means, this definition must result from a complete and systematic process that reflects deep understanding. However, even if this is true as a matter of commonsense, it is also true that this brings with it the same problem. When we think about the means via which we could shape and amplify convergence, we’re still confronted with this move also opening up to the opportunity for divergence. Surely if you asked five experts in the same field how to promote greater agreement about the field’s conceptual fundamentals, in most fields their answers to this “how” question would prove to be very divergent.

When I walk this back to everyday circumstances in which terms/names/concepts and their concomitant definitions are facts of innersubjective assumption rather than innersubjective negotiation, I’d be even more confident that a similar experiment would verify my hunch.

Actually, I informally test this hunch all the time. The main paradox I’ve discovered in doing this is that people speak about shared concepts, (and these concepts implicate shared systems,) without really caring about whether they share the same definitions for these shared concepts. They likely do not share the same definitions! That this underlying disagreement hardly comes to matter is a fascinating element of ‘folk psychological’ behavior and of what could be called intersubjective heuristics.

Consider the beneficial efficiency gained from being able to talk about systems all the while disagreement about basic stuff is underfoot. Whenever I hear the word socialism in our contemporary political discourse, I’m reminded of this paradox of effectiveness.

The Reduced Bateson Set is a heuristic of the kind that are structured and demonstrably pragmatic. The Reduced Bateson Set is my private naming of a pragmatic structure for working through the experience of observing and participating in, learning, inquiry, and dialog. This structure is useful in other interactive circumstances. I’ve named it so because it is my appropriation of stuff reduced from the partial set of Bateson’s ideas I know.