Why Freud Still Matters, When He Was Wrong About Almost Everything io9

George Dvorsky does a good job in his short article aiming to review Freud’s contribution to psychology. Some of the comments are interesting too.

Sigmund Freud Speaks: The Only Known Recording of His Voice, 1938

I lean more toward the structuralism of C.G. Jung than that of Freud, yet, personally, because Freud is the necessary precedent to the ongoing provocations of the post-Freudians, Freud’s contribution remains lively. Also, I’m always reminded the introspective field of the proto-depth ‘psychologies’ suppose such intuitions, elaborations and formulations to be typically phenomenological; and this in turn, has given ordinary folk psychologists–everybody to lesser or greater extent–a vocabulary for talking about our development. Face it, to simulate other minds or intuit other mind’s models, seems yo require something like a set of normative behavioral categories, right?

Is psychoanalysis psychology or poetics?

I came to the article by way of 9 Quarks Daily, and in the comments there was a link to Freudian and Post-Freudian Psychology: A Bibliography Patrick S. O’Donnell. From his excellent essay:

Introduction & Apologia

A New York Times piece by Patricia Cohen, “Freud Is Widely Taught at Universities, Except in the Psychology Department,” summarizes a recent study in The Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association:

“Psychoanalysis and its ideas about the unconscious mind have spread to every nook and cranny of the culture from Salinger to ‘South Park,’ from Fellini to foreign policy. Yet if you want to learn about psychoanalysis at the nation’s top universities, one of the last places to look may be the psychology department. A new report by the American Psychoanalytic Association has found that while psychoanalysis—or what purports to be psychoanalysis—is alive and well in literature, film, history and just about every other subject in the humanities, psychology departments and textbooks treat it as ‘desiccated and dead,’ a historical artifact instead of ‘an ongoing movement and a living, evolving process.’”

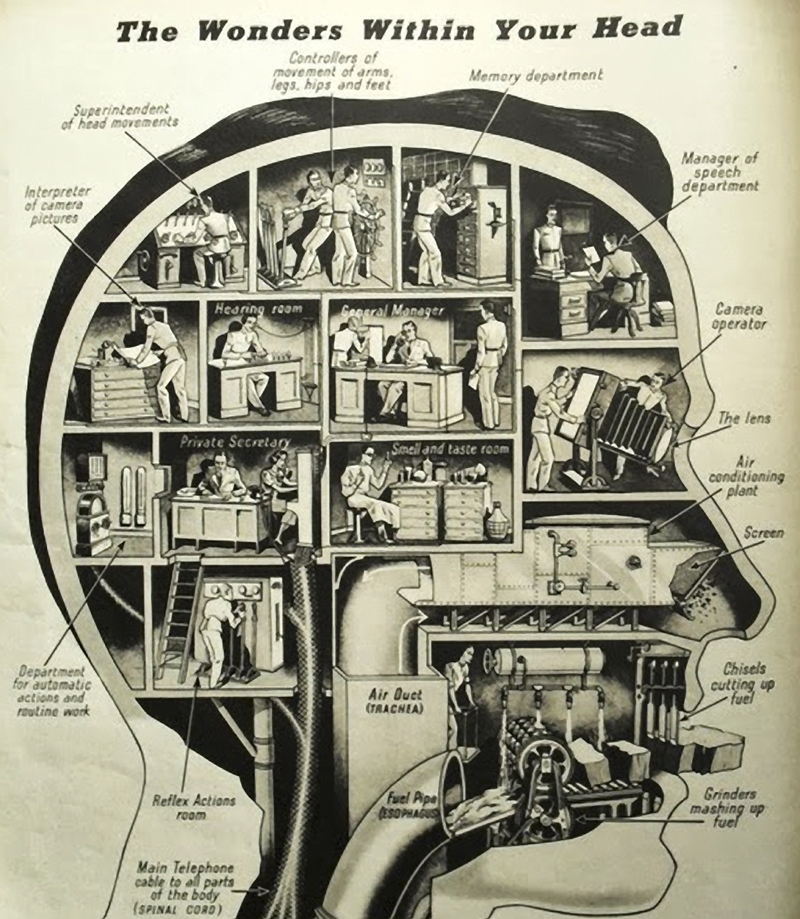

One reason that looms large in accounting for this state of affairs is the extent to which academic psychology in this country conceives itself as a “scientific” enterprise. And inasmuch as this putative psychological science is linked to an experimental and clinical science of health care, it fancies itself grounded in “empirical rigor and testing,” beholden, that is, to what falls under the allegedly rigorous rubric of “evidence-based medicine” (EBM). This conception strives to place psychology on par with other natural sciences and further explains the recent overweening infatuation with neuroscience and the extravagant claims often made on behalf of evolutionary psychology.[1] An ancillary reason involves sceptical disenchantment with the so-called folk theory of mind or folk psychology from not a few quarters in the philosophy of mind (e.g., eliminative materialism).[2]

This is not to insinuate that this folk theory is immune to philosophical revision or extension, but only that any plausible psychological model has compelling reasons for assuming at least some of the key premises that animate this model. Nor is this to imply that psychology can or should ignore science, rather, it may be the case that psychology, insofar as it deals with (a narrative sense of) “the self” and with the nature of mental life, may be better construed as a “science of subjectivity,” wherein science is best understood in an analogical or metaphorical sense, or used simply to refer to a systematic and thus coherent system of inquiry and knowledge (cf. the ‘Islamic sciences’) rather than simply or solely as an objectivist and naturalistic—and frequently positivist—endeavor. Freudian psychology in general and psychoanalysis in particular resist the post-positivist (hence scientistic) “penchant for quantities” and the “fetish for measurement” that infect the natural and social sciences, symptomatic evidence for which is seen in the inordinate fondness for and explanatory and normative privilege accorded to, game theory, cost-benefit calculations, and Bayesian probability estimates (its paradigm of statistical inference serving as the epitome of empirical argument), for example (in saying this, I am not being dismissive of such tools).

In other words, and in the end, Freudian psychology shares with Pragmatism broadly conceived what Hilary Putnam calls the “revolt against formalism:” “This revolt against formalism is not a denial of the utility of formal models in certain contexts; but it manifests itself in a sustained critique of the idea that formal models, in particular, systems of symbolic logic, rule books of inductive logic, formalizations of scientific theories, etc.—describe a condition to which rational thought can or should aspire.” In this case, a condition to which our psychology can or should aspire. To paraphrase and quote again from Putnam, our conceptions of rationality cast a net far wider than all that can be scientized, logicized, mathematized, in short, formalized: “The horror of what cannot be methodized is nothing but method fetishism.”

As for modern scientific psychology, it isn’t very capacious given the total ecology of mental functioning, intentionality, and agency. Nor is it likely ever to be so with respect to being able to, for example, predict everyday behavior. What will Subject A put in their shopping cart?

Elsewhere our groping for understanding remains informed by the remaining, roughly accurate, categories and concepts of depth psychology. These conceptions, etc.. are also revisable.

Poetics?