Gregory Bateson & Margaret Mead, Bajoeng-Gedé, Indonesia; photograph by Walter Spies

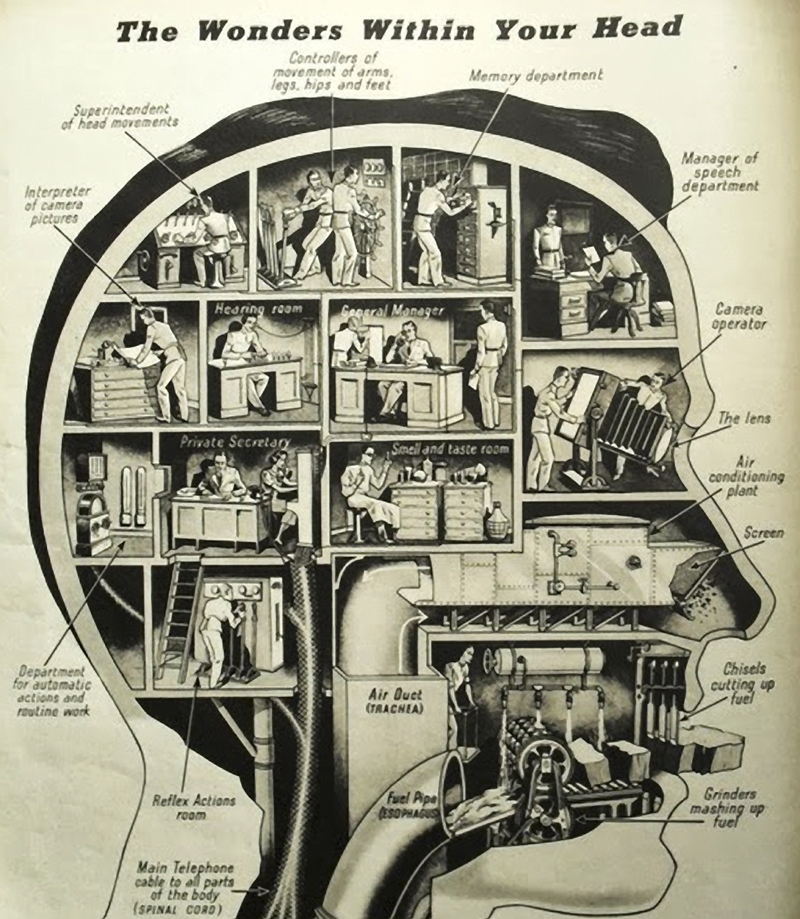

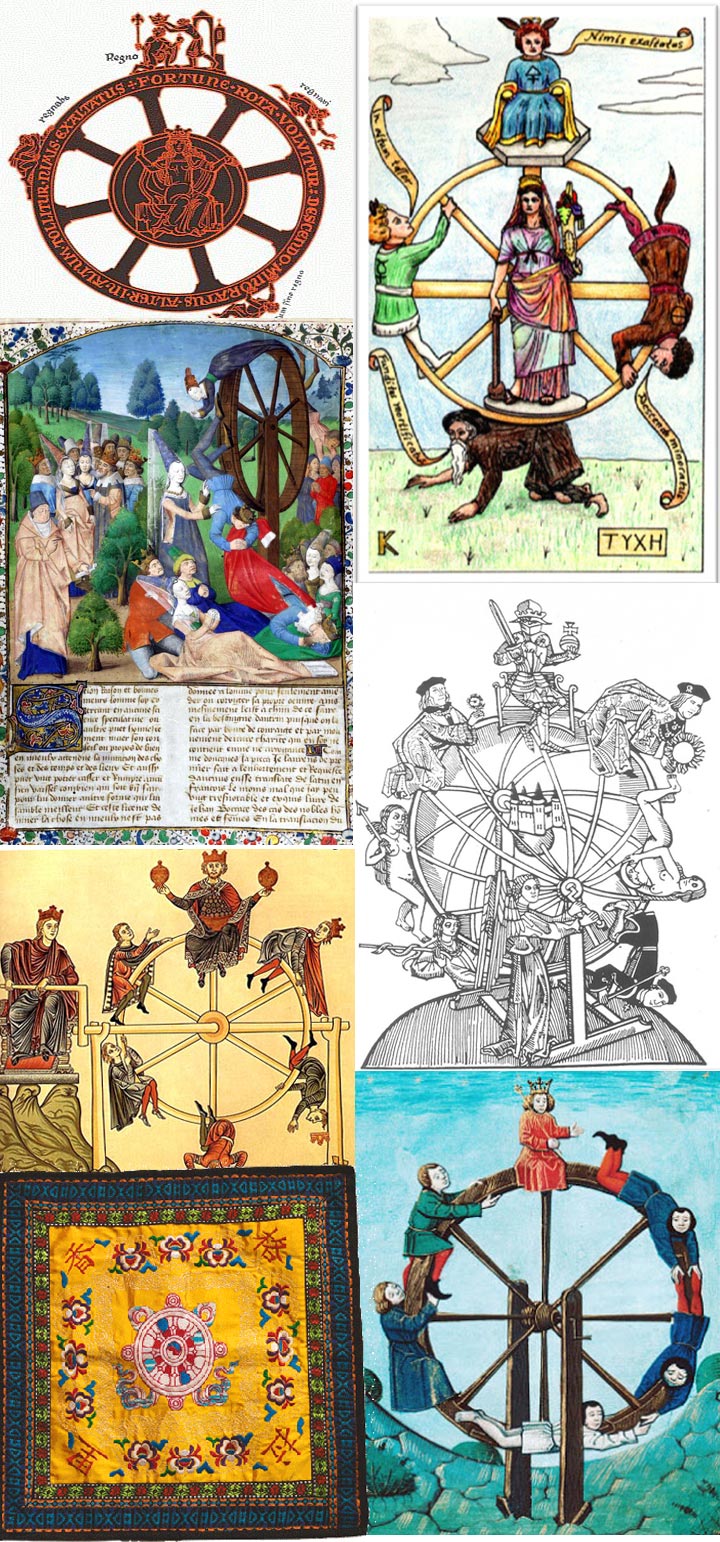

Sometime ago, yet late in my scatter shot intellectual development, I realized five problems fascinated me in psychology. One is the problem of how our brain instantiates and substantiates consciousness. Two is how it came to be that the equivalent of a William James doesn’t arrive much earlier so as to shift proto-psychology forward at an earlier stage in history. This problem wonders about the relationship between culture and contemporaneous psychological categories. The third problem, related to the second problem, is coded (for me) as the problem of introspection. The fourth problem is coded too, as the bundle of problems given by folk psychology at the level of meta-psychology; ie. philosophy of psychology.

And, finally, the fifth problem, very much related to the fourth problem, is the problem of: everyday behavior joined with how psychology’s different disciplines approach everyday behavior as its object of research. I am especially intrigued by how behaviors are named despite those same names being unnecessary to persons behaving in the way the name denotes.

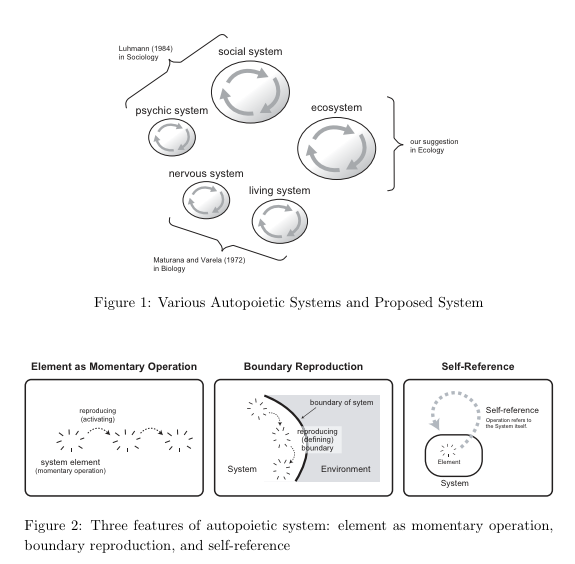

I will seek to explain what I call The Reduced Bateson Set in a series of posts. The Reduced Bateson Set names a framework I utilize. Meanwhile, from an authoritative source:

For the moment, the set-up for this was evoked by my trying to figure out how to describe what is The Reduced Bateson Set. I was moved to look up the definition of heuristic–or rather a definition–in a standard reference book, because I thought this might be the best descriptive term. If so, I could simply say The Reduced Bateson Set is a heuristic I have come to use and favor.

I didn’t think the term was strikingly adequate, inasmuch as I had a deviant definition of heuristic in mind.

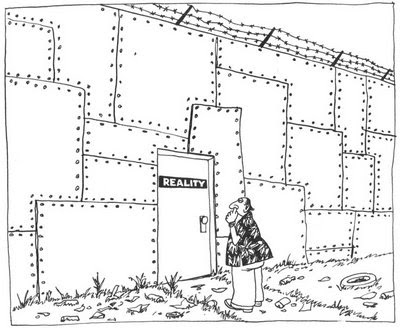

According to the now prevailing definition, heuristics are rather parsimonious and effortless, but often fallible and logically inadequate, ways of problem solving and information processing. A heuristic provides a simplifying routine or “rule of thumb” that leads to approximate solutions to many everyday problems. However, since the heuristic does not reflect a deeper understanding of the problem structure, it may lead to serious fallacies and shortcomings under certain conditions. Thus, in contrast to the positive connotations of the original term, the modern notion of cognitive heuristics has attained the negative quality of a mental shortcut that frees the individual of the necessity to process information completely and systematically. Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Psychology

Okay, my definition turns out to be a bit too innovative! But at least it doesn’t imply a ridiculous optimal “problem solving.”

More precisely to the point here, is how rapidly I landed in a Batesonian moment. Unfolded in the encyclopedia entry is a long treatment of the term, yet, it’s not describing much about what I wish to also describe. And, the problem could be that it could not describe even what it seeks to describe–in a deep sense able to capture something very very common.

What is this something? It is that some large portion, possibly a majority portion, of human behavior is “heuristical.” Which is to suggest: it is likely a majority of human problem solving, leaarning, discovery, etc., everyday, (every darn day,) processes information incompletely and not systematically. Also, a corollary to this is: some large portion of human problem solving cannot access both a totality of pertinent information, or, have been the subject of a complete processing within, I suppose, a formal requirement for complete and systematic processing.

Wikipedia’s entry is not robust, but it is more satisfying.

Heuristic (pronounced /hj??r?st?k/) or heuristics (from the Greek “???????” for “find” or “discover”) refers to experience-based techniques for problem solving, learning, and discovery. Heuristic methods are used to come to an optimal solution as rapidly as possible. Part of this method is using a “rule of thumb”, an educated guess, an intuitive judgment, or common sense. A heuristic is a general way of solving a problem.

Except I will quarrel with it too. I don’t know the correct term for that which is a precise and focused heuristic way of solving particular everyday problems. Yet, I do understand the ‘human everyday’ presents a series of opportunities to problem solve, learn, and discover. Figuring out what you’re going wear is a particular problem, and a problem I’d suppose is solved in precise and focused ways.

(Perhaps a differentiation made among general, and, ‘problem-particular,’ methods is unnecessary.)

Among, (what I will term Batesonian,) distinctions found in definitions is this hot one. First, to develop a correct definition is itself a problem to be solved. Could it be demonstrated that any given normative (or authoritative) definition was created, subject to heuristics? Here of course I’m speaking of an example, the definition of heuristic. A second Batesonian distinction is implicit in speaking of the possible heuristics behind the term heuristic.

Here’s a doable experiment. Collect five of the foremost social psychologists together and have them each write out their definition of the term, heuristic. Assume there is a sound method for scoring to what degree the five definitions match up. For my argument here, let’s assume the result of this experiment shows a very high degree of matching.

The five world class experts are then asked to do the following: “How do you know your definition is the correct definition?” Score the answer.

Let’s do this same experiment and add the following parameter. Before either primary question is addressed, each group member is asked the following: “How many pages will you need to answer the question, How do you define heuristic?” Allow no limit in length for their written answers.

Hypotheses are to be entertained. I won’t offer these, yet I will suppose the results of this experiment will

demonstrate considerable disagreement on question number two, How do you know your definition is the correct definition, and this disagreement increases the longer any answer is to either question. So, the most disagreement would be found between the longest answers.

There’s a problem incurred by my supposing the answers could be scored. How would we score different points of emphasis? Those points could not be scored as only disagreements. Still, our scoring would have to resolve this problem in reckoning with matching points of emphasis and divergent points of emphasis.

My hunch that there would be found disagreement is, obviously, completely a matter of a decidedly intuitive and heuristic approach to thinking about the problem of defining a normative term. What I’m thinking about here is the human system able to develop useful definitions about its own features. The experiment might well defeat my hunch. But, what if the experiment proved the underlying hypotheses?

What then could be suggested by the results of this experiment about hypothesized deviations from agreement? What also could be suggested about how the problem of expert definition is approached by experts? Do these experts employ heuristics as an effective, or not effective, means?

Consider a countervailing–with respect to my hunch–supposition. That: in a description, where detail increases, deviations are reduced. (Speaking of building houses: we can all agree on the sharp nail and the straight board.) This suggests that as descriptions penetrate ‘down’ to more elemental levels of order in a system, deviations between descriptions are reduced.

My hunch asserts the opposite is possibly the experimental result. So: as experts expert in the same system propose descriptions of this system, as the level of detail increases in their descriptions, their descriptions will tend to diverge.

Again, a countervailing supposition might be rooted in the same idea given in the Blackwell encyclopedia: to define a system correctly, and so free the definition from any reliance on heuristic means, this definition must result from a complete and systematic process that reflects deep understanding. However, even if this is true as a matter of commonsense, it is also true that this brings with it the same problem. When we think about the means via which we could shape and amplify convergence, we’re still confronted with this move also opening up to the opportunity for divergence. Surely if you asked five experts in the same field how to promote greater agreement about the field’s conceptual fundamentals, in most fields their answers to this “how” question would prove to be very divergent.

When I walk this back to everyday circumstances in which terms/names/concepts and their concomitant definitions are facts of innersubjective assumption rather than innersubjective negotiation, I’d be even more confident that a similar experiment would verify my hunch.

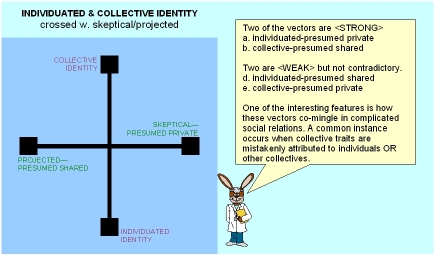

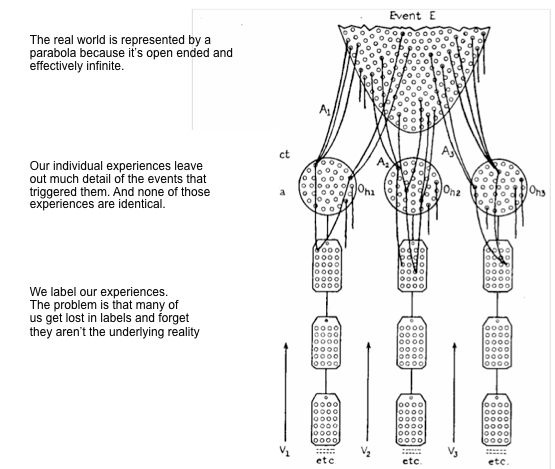

Actually, I informally test this hunch all the time. The main paradox I’ve discovered in doing this is that people speak about shared concepts, (and these concepts implicate shared systems,) without really caring about whether they share the same definitions for these shared concepts. They likely do not share the same definitions! That this underlying disagreement hardly comes to matter is a fascinating element of ‘folk psychological’ behavior and of what could be called intersubjective heuristics.

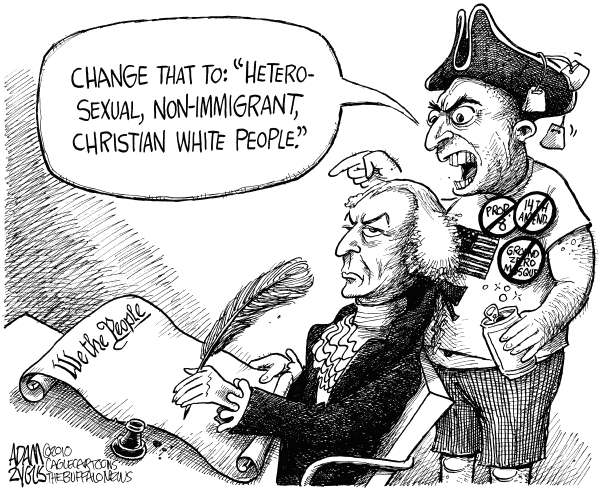

Consider the beneficial efficiency gained from being able to talk about systems all the while disagreement about basic stuff is underfoot. Whenever I hear the word socialism in our contemporary political discourse, I’m reminded of this paradox of effectiveness.

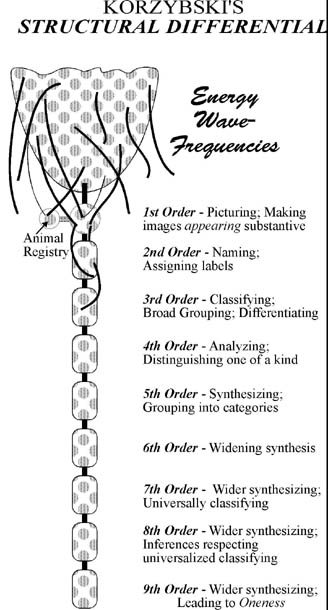

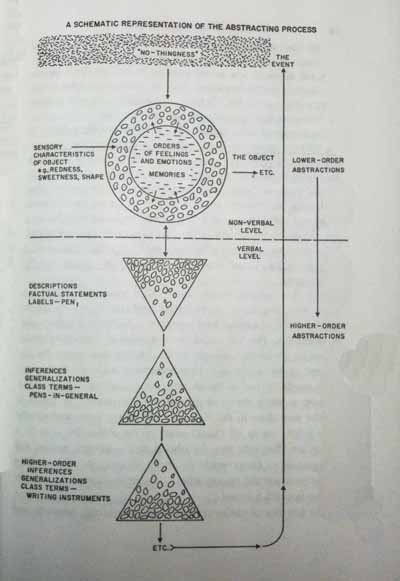

The Reduced Bateson Set is a heuristic of the kind that are structured and demonstrably pragmatic. The Reduced Bateson Set is my private naming of a pragmatic structure for working through the experience of observing and participating in, learning, inquiry, and dialog. This structure is useful in other interactive circumstances. I’ve named it so because it is my appropriation of stuff reduced from the partial set of Bateson’s ideas I know.

Kizzy and Sonny. Kizzy (from Kismet) was a stray kitten that found her way to our back door. I would guess our back door is the best back door for a stray to come up to! Sonny’s story is not dissimilar. While visiting the veterinarian with our two older cats, we noticed a kitten on the counter in the waiting area. Hard to miss! We learned somebody had left three kittens in a box in the parking lot the day before. With that the aid plucked a bluff colored kitten out of a waste basket full of shredded paper, and told us, “This one is spoken for!” Soon enough he was spoken for, and so Sonny comes home,

Kizzy and Sonny. Kizzy (from Kismet) was a stray kitten that found her way to our back door. I would guess our back door is the best back door for a stray to come up to! Sonny’s story is not dissimilar. While visiting the veterinarian with our two older cats, we noticed a kitten on the counter in the waiting area. Hard to miss! We learned somebody had left three kittens in a box in the parking lot the day before. With that the aid plucked a bluff colored kitten out of a waste basket full of shredded paper, and told us, “This one is spoken for!” Soon enough he was spoken for, and so Sonny comes home,