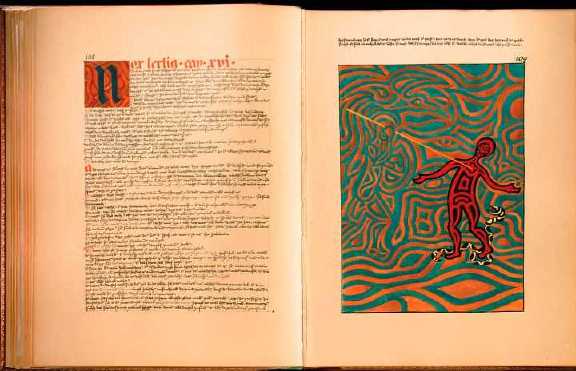

Sara Corbett, writing in the Sunday New York Times Magazines, tells the story of the publication of Carl Jung’s most prominent, heretofore unpublished, work, The Red Book. The Holy Grail of the Unconscious

Seeing the article trumpeted on the magazine’s front page, then slowly taking in photos of several two page layouts, and then, finally, reading the article carefully, made for an unanticipated pleasure on a Sunday afternoon.

Although the story is a good one, here I’ll highlight the author’s summary of part of Dr. Jung’s long (1975-1961) life.

Carl Jung founded the field of analytical psychology and, along with Sigmund Freud, was responsible for popularizing the idea that a person’s interior life merited not just attention but dedicated exploration — a notion that has since propelled tens of millions of people into psychotherapy. Freud, who started as Jung’s mentor and later became his rival, generally viewed the unconscious mind as a warehouse for repressed desires, which could then be codified and pathologized and treated. Jung, over time, came to see the psyche as an inherently more spiritual and fluid place, an ocean that could be fished for enlightenment and healing.

Whether or not he would have wanted it this way, Jung — who regarded himself as a scientist — is today remembered more as a countercultural icon, a proponent of spirituality outside religion and the ultimate champion of dreamers and seekers everywhere, which has earned him both posthumous respect and posthumous ridicule. Jung’s ideas laid the foundation for the widely used Myers-Briggs personality test and influenced the creation of Alcoholics Anonymous. His central tenets — the existence of a collective unconscious and the power of archetypes — have seeped into the larger domain of New Age thinking while remaining more at the fringes of mainstream psychology.

A big man with wire-rimmed glasses, a booming laugh and a penchant for the experimental, Jung was interested in the psychological aspects of séances, of astrology, of witchcraft. He could be jocular and also impatient. He was a dynamic speaker, an empathic listener. He had a famously magnetic appeal with women. Working at Zurich’s Burghölzli psychiatric hospital, Jung listened intently to the ravings of schizophrenics, believing they held clues to both personal and universal truths. At home, in his spare time, he pored over Dante, Goethe, Swedenborg and Nietzsche. He began to study mythology and world cultures, applying what he learned to the live feed from the unconscious — claiming that dreams offered a rich and symbolic narrative coming from the depths of the psyche. Somewhere along the way, he started to view the human soul — not just the mind and the body — as requiring specific care and development, an idea that pushed him into a province long occupied by poets and priests but not so much by medical doctors and empirical scientists.

That’s a fairly good recap.

“Venus” figurine. Est. 35,000 years old.

I’m looking forward to receiving another visitation from Dr. Jung.

Certainly there is no figure in the history of ideas about human nature with whose work I have spent more time. On the other hand, I’m long past my enchantment with Jung and Analytic Psychology. My relationship is complicated. Suffice to say, some of the concepts concerned with everyday patterns of human nature, (meaning: the flux of experience, introspection, perception, and behavior,) continue to resonate and thus are useful, whilst the more systematic aspects have lost both their charge and most of their value.

At least I can explain this differentiation (and my evaluation,) to my own personal satisfaction. A lot of research and wandering caused my stepping forward–away from Jung and Freud and other quaint artifacts of the psycho-dynamic turn in 20th century psychology. In the main, the biggest factor was my coming to appreciate the sweep of psychology that came after Jung.

“Mammoth” figurine. Est. 35,000 years old.

However, as a vehicle for poetical self-artistry and introspective exploration, its pragmatic tools, for me, remain very keen. The inner work is to be canny.

There are, in my way of looking at an over-arching scheme about human consciousness, at least a half dozen great questions.

1. What is the nature of human consciousness?

2. What is the nature of its mediation via relations with other minds?

3. What is the nature of apprehension of the environment-world-cosmos?

4. What is the nature of introspection?

5. What is the nature of learning?

6. What is the nature of creativity?

Although naturalistic disposition is plugged into each question, purposely I have not further qualified any prospective answers to be only: scientific, or rational, or artistic, etc.. Nor would I suppose any answer must be objective. After all, “the psyche is the greatest of all cosmic wonders,” (Jung.) Touch the elephant from where you are, and tell me what the feel is! I’m actually most interested in how any given individual might address such questions, or, how he or she might otherwise express what these and related questions evoke. Among my favorite answers are those sounded by Thelonious Monk; for example. To my sensibility, Monk’s answers are far superior to those offered by Paul Churchland! ;-)

Shells beads escavated in Morocco. Est. 75,000+ years old.

Carl Jung obviously was concerned with these questions, and, he also brought into play a number of very deep questions about human development into play. That he developed a vast, even comprehensive value-laden, developmentally-oriented system out of his own experiential and deeply humane learning, is one of the most remarkable instances of human inquiry and creativity and articulation of knowledge.

I suspect the Red Book will provide almost an overwhelmingly intimate ride with the good doctor. I also suppose there’s no way to ready one’s self for such a visitor.

One repays a teacher badly if one remains only a pupil.

And why, then, should you not pluck at my laurels?

You respect me; but how if one day your respect should tumble?

Take care that a falling statue does not strike you dead!

You had not yet sought yourselves when you found me.

Thus do all believers–.

Now I bid you lose me and find yourselves;

and only when you have all denied me will I return to you.

(Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, quoted Jung to Freud, 1912)