The risk of inner experience, the adventure of the spirit, is in any case alien to most human beings. ~Carl Jung; Memories, Dreams and Reflections

The risk of inner experience, the adventure of the spirit, is in any case alien to most human beings. ~Carl Jung; Memories, Dreams and Reflections

Print out this post to utilize the two assessment forms.

Archetype Axis

Reflect on the make-up of your personality and assign 15 total points to select archetypal aspects. The scale of the point system is graded this way:

4 points – most dominant expression of particular archetypal element

3 points – next most dominant expression

2 points – strong expression

1 point – mild expression

Use the following distribution protocol:

Assign 4 points once

Assign 3 points once

Assign 2 points at least once

Assign 1 point

Use no more than 15 total points.

Kolb Learning Style ‘array’

Reflect on the make-up of your personality and assign 15 total points to select archetypal aspects. The scale of the point system is graded this way:

4 points – most dominant expression of particular learning disposition element

3 points – next most dominant expression

2 points – strong expression

1 point – mild expression

Use the following distribution protocol:

Assign 4 points once

Assign 3 points once

Assign 2 points at least once

Assign 1 point

Use no more than 12 total points.

Example (my own)

note-I am misusing the Kolb Style array. However, my redeployment of it as a device for self-evaluation does provide me the means to better assert stylistic disposition in relationship to actual concrete learning contexts. The example here is generalized but takes into account–in a phenomenological sense–my real time introspective intuition on the nature of my own learning process. This is a more accurate process of evaluation than the formal instrument allows for.

Dear Mr. Harrison

the problem of the Ufos is, as you rightly say, a very fascinating one, but it is as puzzling as it is fascinating; since, in spite of all observations I know of, there is no certainty about their very nature. On the other side, there is an overwhelming material pointing to their legendary or mythological aspect. As a matter of fact the psychological aspect is so impressive, that one almost must regret that the Ufos seem to be real after all. I have followed up the literature as much as possible and it looks to me as if something were seen and even confirmed by radar, but nobody knows exactly what is seen. In consideration of the psychological aspect of the phenomenon I have written a booklet about it, which is soon to appear. It is also in the process of being translated into English. Unfortunately being occupied with other tasks I am unable to meet your proposition. Being rather old, I have to economize my energies.Carl Jung

Filed under philosophy, psychology, science

Carl Gustav Jung and Friedrich Hayek.

I had occasion to contribute to the Jung-Circle discussion group the following cut from The Symbolic Life, and, with it, this comment: “It would be a worthwhile study to investigate the definite, and considerable, overlap between Jung’s suppositions and those of the Austrian school of economics, (Hayek and Von Mises.)”

Together with these illusions goes another helpful procedure, the hollowing out of money, which in the near future will make all savings illusory and, along with cultural continuity, guaranteed by individual responsibility. The State takes over responsibility and enslaves every individual for its own ridiculous schemes. All this is done by what one calls inflation, devaluation, and, most recently, “dilution,” which you should not mix up with the unpopular term “inflation.” Dilution is now the right word and only idiots can’t see the striking difference between this concept and inflation. Money value is fast becoming a fiction guaranteed by the State. Money becomes paper and everybody convinces everybody else that the little scraps are worth something because the State says so. (C.G. Jung; Psychology and National Problems (1936) The Symbolic Life

My comment was unrefined. Actually, given the essential psychologizing move at the first order of Austrian Economics, and, the explicit radically empirical posit of classical Analytic Psychology, their conceptualization of human behavior depart from each other right at their beginning. They are similar in their anti-scientism, in their view of the inherent limits to quantification, and, in their broad thrust favoring individuality in response to their dissimilar foundational conception of the dichotomy, individual/collective.

Allegiance to Praxeology, (the deduced axioms of human action in Austrian Economics,) is behaviorally subject to archetypal analysis. The psychology of the person who is in the grips of their belief in this particular axiom-driven system is interesting. Jung would likely have found attachment to the praxeological system, for which, as Hayek asserted, empiricism and facts are of no import to be particularly laden with unconscious features.

Ironically, and pun intended, the Praxeology could be said to be about inflation.

Criticism of the basic, and partly shared, dichotomy at the center of each system, were of no interest to Hayek, von Mises, or Dr. Jung. Although, to the latter’s credit, the evolutionary, intrapsychic, core structural supposition, the collective unconscious, is a ‘social’ conception. The two frameworks are opposite one anther at this level of genetic supposition.

(coda) C.G. Jung:

Can there be an optimism of austerity?

Instead of “optimism,” I would have said an “optimum” of austerity. But if “optimism” is really meant, very much more would be required, for “austerity” is anything but enjoyable. It means real suffering, especially if it assumes acute form. You can be “optimistic” in the face of martyrdom only if you are sure of the bliss to come. But a certain minimal degree of austerity I regard as beneficial. At any rate, it is healthier than affluence, which only a very few people can enjoy without ill effects, whether physical or psychic. Of course one does not wish anything unpleasant for anybody, least of all oneself, but, in comparison with other countries, Switzerland has so much affluence to spare (however honourably earned) that we are in an excellent position to give some of it away. There is an “optimum” of austerity which it is dangerous to exceed, for stands a devll, and behind every poor man two.Since “optimism” seems to have been meant, and hence an optimistic attitude towards something unpleasant, I would add that in my view it would be equally instructive to speak of a “pessimism” of austerity. Human temperaments being extremely varied, indeed contradictory, we should never forget that what is good for one man is harmful for another. One man, because of his inner weakness, needs encouragement; another, because of his inner assurance, needs the restraint of austerity. Austerity enforces simplicity, which is true happiness. But to live simply, without regret and bitterness, is a moral task which many people will find very hard. (Return to the Simple Life; 1941; The Symbolic Life)

Filed under analytic(al) psychology

How to hold the tension of the opposites?

Following from the everyday experience of conflict, or dissonance, or intense ambivalence, Carl Jung doesn’t treat experiential matters like this often. The basic reason is a little bit below the surface of this typical statement from Aion,

“Most people do not have sufficient range of consciousness to become aware of the opposites inherent in human nature. The tensions they generate remain for the most part unconscious, but can appear in dreams.”

With this statement, we’re no longer in the realm of the everyday sundry betwixt and betweens.

The core opposition in Analytic Psychcology is consciousness/unconsciousness. To ask ‘how to hold the tension of opposites’ strikes me as a modern request for a “self-helpful” instrumental technique, as against the energetic, (what for me is a libido or hydraulic,) model given in the classical version, and in Jung’s understanding, of the psyche. In this latter model, the problem is extant in an energized intrapsychic field of energy. This field is the territorial locus for the complex compression given in the intrapsychic confrontation between the known, nascent self-knowledge, and, the unknowable.

Although Dr. Jung does not use the term tension of the opposites much, and does not offer any ‘self-help’ on the ‘how,’ there are several detailed treatments scattered in his writings.

First, Two Essays In Analytic Psychology, (CW 7; 4th ed. 1966) is much about the opposites.

This example clearly shows that it does not lie in our power to transfer “disposable” energy at will to a rationally chosen object. The same is true in general of the apparently disposable energy which is disengaged when we have destroyed its unserviceable forms through the corrosive of reductive analysis. This energy, as we have said, can at best be applied voluntarily for only a short time. But in most cases it refuses to seize hold, for any length of time, of the possibilities rationally presented to it. Psychic energy is a very fastidious thing which insists on fulfilment of its own conditions. However much energy may be present, we cannot make it serviceable until we have succeeded in finding the right gradient.

This question of the gradient is an eminently practical problem which crops up in most analyses. For instance, when in a favourable case the disposable energy, the so-called libido, does seize hold of a rational object, we think we have brought about the transformation through conscious exertion of the will. But in that we are deluded, because even the most strenuous exertions would not have sufficed had there not been present at the same time a gradient in that direction. How important the gradient is can be seen in cases when, despite the most desperate exertions, and despite the fact that the object chosen or the form desired impresses everybody with its reasonableness, the transformation still refuses to take place, and all that happens is a new repression.

It has become abundantly clear to me that life can flow forward only along the path of the gradient. But there is no energy unless there is a tension of opposites; hence it is necessary to discover the opposite to the attitude of the conscious mind. It is interesting to see how this compensation by opposites also plays its part in the historical theories of neurosis: Freud’s theory espoused Eros, Adler’s the will to power. Logically, the opposite of love is hate, and of Eros, Phobos (fear); but psychologically it is the will to power. Where love reigns, there is no will to power; and where the will to power is paramount, love is lacking. The one is but the shadow of the other: the man who adopts the standpoint of Eros finds his compensatory opposite in the will to power, and that of the man who puts the accent on power is Eros. Seen from the one-sided point of view of the conscious attitude, the shadow is an inferior component of the personality and is consequently repressed through intensive resistance. But the repressed content must be made conscious so as to produce a tension of opposites, without which no forward movement is possible. The conscious mind is on top, the shadow underneath, and just as high always longs for low and hot for cold, so all consciousness, perhaps without being aware of it, seeks its unconscious opposite, lacking which it is doomed to stagnation, congestion, and ossification. Life is born only of the spark of opposites. (L76-78)

The tension of the opposites, in being sparked, is unbidden. In the classical view, it is not subject to the ‘how’ given by our modern self-help view. Thus, to be in the psychological problem so sparked is to be in a situation for which a fruitful appeal may be made to an analytic relationship–through which the working creatively or waiting creatively through the (variously) phantasy/symbolic/dream/actively imagined material, is the means of holding material energized in the ineluctable terms of this gradient.

The problem of opposites, as an inherent principle of human nature, forms a further stage in our process of realization. As a rule it is one of the problems of maturity. The practical treatment of a patient will hardly ever begin with this problem, especially not in the case of young people. The neuroses of the young generally come from a collision between the forces of reality and an inadequate, infantile attitude, which from the causal point of view is characterized by an abnormal dependence on the real or imaginary parents, and from the teleological point of view by unrealizable fictions, plans, and aspirations.

Elsewhere Jung states “the opposites condition each other.” The youthful conditioning movement (or energetics, libido,) settles out the persona, distills the egoic first person, and, next may confront the repression of the Shadow.

Here the reductive methods of Freud and Adler are entirely in place. But there are many neuroses which either appear only at maturity or else deteriorate to such a degree that the patients become incapable of work. Naturally one can point out in these cases that an unusual dependence on the parents existed even in youth, and that all kinds of infantile illusions were present; but all that did not prevent them from taking up a profession, from practicing it successfully, from keeping up a marriage of sorts until that moment in riper years when the previous attitude suddenly failed. In such cases it is of little help to make them conscious of their childhood fantasies, dependence on the parents, etc., although this is a necessary part of the procedure and often has a not unfavourable result. But the real therapy only begins when the patient sees that it is no longer father and mother who are standing in his way, but himself-i.e., an unconscious part of his personality which carries on the role of father and mother. Even this realization, helpful as it is, is still negative; it simply says, “I realize that it is not father and mother who are against me, but I myself.” But who is it/in him that is against him? What is this mysterious part of his personality that hides under the father and mother-imagos, making him believe for years that the cause of his trouble must somehow have got into him from outside? This part is the counterpart of his conscious attitude, and it will leave him no peace and will continue to plague him until it has been accepted.

Acceptance.

What youth found and must find outside, the man of life’s afternoon must find within himself. Here we face new problems which often cause the doctor no light headache.

The transition from morning to afternoon means a revaluation of the earlier values. There comes the urgent need to appreciate the value of the opposite of our former ideals, to perceive the error in our former convictions, to recognize the untruth in our former truth, and to feel how much antagonism and even hatred lay in what, until now, had passed for love. Not a few of those who are drawn into the conflict of opposites jettison everything that had previously seemed to them good and worth striving for; they try to live in complete opposition to their former ego. Changes of profession, divorces, religious convulsions, apostasies of every description, are the symptoms of this swing over to the opposite. The snag about a radical conversion into one’s opposite is that one’s former life suffers repression and thus produces just as unbalanced a state as existed before, when the counterparts of the conscious virtues and values were still repressed and unconscious. Just as before, perhaps, neurotic disorders arose because the opposing fantasies were unconscious, so now other disorders arise through the repression of former idols. It is of course a fundamental mistake to imagine that when we see the non-value in a value or the untruth in a truth, the value or the truth ceases to exist. It has only become relative. Everything human is relative, because everything rests on an inner polarity; for everything is a phenomenon of energy. Energy necessarily depends on a pre-existing polarity, without which there could be no energy. There must always be high and low, hot and cold, ete., so that the equilibrating process–which is energy–can take place. Therefore the tendency to deny all previous values in favour of their opposites is just as much of an exaggeration as the earlier one-sidedness. And in so far as it is a question of rejecting universally accepted and indubitable values, the result is a fatal loss. One who acts in this way empties himself out with his values, as Nietzsche has already said. (214-215)

Acceptance and recognition, and, in that order. Again, there is not in the classic perspective any explicit ‘self-help’ advice. Holding is how, and this may mean allowing for the problem to stay, for it to be sticky and to be stuck to it. The underlying energetic circumstance demands the ego with its charge, or libido, to appropriate more than enough consciousness to enter into relation/relatedness with the charged opposite, accept, recognize, and, equilibrate at a higher key.

Because the classic and ensuing revisions of the model of the psyche of Analytic Psychology is problematic in light of modern psychology, in backing away in the direction of common situations of psychological conflict, be these the stuckedness given by conflicts of emotion, cognition, aspiration, it is easy enough for me, grounded in models of adult learning, to comprehend the similarity to how change comes about in experiential learning, where the phase of resolution describes our effectiveness in either adapting our self to the circumstance, or, altering the external circumstance to our self.

***

Numerous teaching stories, the koan, and aphorisms that drill right to the tense middle. My favorite is an aphorism of Rumi.

What is essential is not important,

what is important is not essential.

There is no way to penetrate this aphorism’s value without feeling and experiencing the tension between essential and important.

When Shams, Rumi’s mentor and beloved, was killed, for Rumi, Shams was gone only in one respect. In the working through the opposite between lover and disappeared beloved, his mature mystic outlook was evoked; love in this case growing despite the profoundly frustrating loss of the beloved’s incarnate being. (And, so Rumi’s mysticism offers a yoga of the opposites, of loss and recognition.)

My own experience is that holding the tensions is an everyday opportunity. Anytime we sacrifice our weak or strong preference, we’re “there” holding for a moment the tension of the opposites. Sometimes it can be helpful to understand what the experience is like by working back from the one-sided beginning or ending. The answer, nevertheless, is given by feeling through the experience–or at least this is my suggestion here.

Putting acceptance before recognition is a subtle insight. This means that the first move in the direction of both greater consciousness and toward distant resolution is to accept the intense frustration, and do this for the sake of being able to then accept the weak formations one may apprehend at the very start. Later, when something like clarity is born in a process of creative working/waiting through the tension of the opposites, the hint of resolution comes to become persistent enough to recognize, and, this recognition comes to comprise a foundation for a new attitude.

Filed under analytic(al) psychology

(First part of two; reworked from an response offered to Jung-Fire, an email discussion group mostly about Analytic Psychology and Carl Jung. These two parts are in response to the question, how do you hold the tension of the opposites?)

Your question is interesting to me because it points in the direction of a practical answer. After all, we know what it is to hold and experience tension. There are common experiences for which a person finds themselves between or betwixt two competing poles. There are also common ways to describe the genre of such situations.

For example, one wants something but can’t have it. One has a problem or challenge but doesn’t really want to meet it. One prefers an easy route and also knows the route is necessarily not easy.

What is meant by experiencing the opposites? A practical answer is rooted in the experiential, and by reflection on experience.

Holding the opposites is a common experience of being human. Yet, those experiences are mostly different than the experience implied by holding the tension of the opposites given in a situation of individuation; individuation being a conspecific of development in the framework of Analytic Psychology.

Let’s consider this first part to be concerned with the normal, common kinds of experiences.

There are many examples and the several I’ll pose address the question indirectly by implicitly asking what does the experience feel like? The “how” is an answer given by thoroughly sensing what the experience feels like.

Say, you’re driving and somebody else on the road makes an idiotic move, and you find yourself being angry. I might in fact mutter ‘you idiot!’ yet, after all, I’m driving, capable of such moves myself, and, my emotional reaction soon enough passes. There: in the middle, and this would be different from the one-sidedness of speeding up and coming next to the other driver and glaring or, umm, raising a digit in protest.

What does it feel like, for example, to estimate almost instantly, the pressures surrounding bursting through the end of the yellow light?

Another basic form of holding opposites is anytime we find our self having to do something we don’t want to do, but, going “through” our objection to then do it.

A ripe example of this is being on either the delivering or receiving end of a romantic break-up. Being on the receiving end is ripest of all because quite often the severing of attachment leaves one in the predicament–again in the middle as it were–between desiring to remain attached and, often suddenly, having this desire absolutely frustrated. This can be very concrete: wanting versus abruptly this desire no longer being able to be fulfilled.

What is this experience?

In reflecting upon what the experience of this kind of tension is, there are several basic descriptive categories. So, our report about our experience could note the experience feels like being pulled in two seemingly mutually exclusive directions. We might then be able to describe what the emotional or affective content of this experience is; we can name its features. Similarly, we can describe cognitively dissonant, or ideational, conflict. Such conflicts are inflected or otherwise weighted by energetic emotions.

Being in the middle is an energetic situation or position.

The psychological problem evoked by this being in the middle, and this middle having come upon us, constitutes resistance of some sort.

There can be resistance to fate, or denial of the actual situation. One can be in the middle–between the fate we’d prefer, and the fate we’re delivered to. The former fate in effect being the movie we’d like to sit through, the latter being the movie we can’t escape.

Asking again, what does this experience feel like? As we develop clues, and better, about this, we come to understand the various processes which take the general form: equilibrium/disruption/tensile conflict/resolution/equilibrium.

Filed under analytic(al) psychology

Anima and Animus (S.Calhoun, 2010)

More ARK, albeit two frames here are layered and treated via software. (chosen, appropriated frames: using Dreamlines; hat tip to Leonardo Solaas)

This ARK art came together while I was revisiting original sources for understanding the concept of the Collective Unconscious in the Analytic Psychology. In other words: I went to confirm my sense was correct, and it was. It was as simple as I thought it was. (I was moved to do so by observing unnecessary elaboration and subsequent projection of this elaboration.) I did a little more scouring around the secondary literature, all the time keeping in mind the basic rock-bottom conception, the Collective Unconscious is that which is neither conscious, or, is “of” the personal unconscious.

Jung’s development of his psychology makes its sea change upon this concept. The Collective Unconscious is the source for the primordial patterns, the archetypes–and, well, so it went and goes. At the same time, the concept–taken as a proposition–is marvelously and completely circular. Most of Jung’s extrapolations made from his fundamental concept have been stripped away, yet, at the end of Jung’s day, this is the basis for his being a holist, a subjectivist, and, a meta-relativist. …sort of a Swiss William James; and given by this it can said Jung was a kind of proto-post-modernist too.

This is easily rendered: there is no knowledge not darkened and come to be provisional by virtue of its ground in the (evolutionary!) Collective Unconscious. One notes the implicit circularity implicit here.

(Among my gleanings was a fine paper by George Hogenson, The Baldwin effect: a neglected influence on C.G. Jung’s evolutionary thinking. Journal of Analytical Psychology; 48:2001)

For a certain type of intellectual mediocrity characterized by enlightened rationalism, a scientific theory that simplifies matters is a very good means of defence because of the tremendous faith modern man has in anything which bears the label “scientific.” Such a label sets your mind at rest immediately, almost as well as Roma locuta causa finita: “Rome has spoken, the matter is settled.” In itself any scientific theory, no matter how subtle, has, I think, less value from the standpoint of psychological truth than religious dogma, for the simple reason that a theory is necessarily highly abstract and exclusively rational, whereas dogma expresses an irrational whole by means of imagery. This guarantees a far better rendering of an irrational fact like the psyche. Moreover, dogma owes its continued existence and its form on the one hand to so-called “revealed” or immediate experiences of the “Gnosis” for instance, the God-man, the Cross, the Virgin Birth, the Immaculate Conception, the Trinity, and so on, and on the other hand to the ceaseless collaboration of many minds over many centuries. It may not be quite clear why I call certain dogmas “immediate experiences’ since in itself a dogma is the very thing that precludes immediate experience. Yet the Christian images I have mentioned are not peculiar to Christianity alone (although in Christianity they have undergone a development and intensification of meaning not to be found in any other religion). They occur just as often in pagan religions, and besides that they can reappear spontaneously in all sorts of variations as psychic phenomena, just as in the remote past they originated in visions, dreams, or trances. Ideas like these are never invented. They came into being before man had learned to use his mind purposively. Before man learned to produce thoughts, thoughts came to him. He did not think he perceived his mind functioning. Dogma is like a dream, reflecting the spontaneous and autonomous activity of the objective psyche, the unconscious. Such an expression of the unconscious is a much more efficient means of defence against further immediate experiences than any scientific theory.The theory has to disregard the emotional values of the experience. The dogma, on the other hand, is extremely eloquent injust this respect. One scientific theory is soon superseded by another. Dogma lasts for untold centuries. The suffering God-Man may be at least five thousand years old and the Trinity is probably even older. (C.G. Jung; Psychology of Religion East and West; pp45-46)

Filed under analytic(al) psychology

For me, Jung’s conception of the collective unconscious is not essential to a comprehensive perspective concerned with how it is symbols, meaningfulness, and evocative patterns are necessary to, and featured in, human personal and social generativity.

Beyer, in his fine overview, gently presents an obvious critique. I’ve excerpted below Beyer on James Hillman.

Just how many archetypes are there? There appears to be no constraint on their number or nature. Steven Walker, a scholar of comparative literature sympathetic to Jung, says that “the list of archetypes is nearly endless.” There can be an archetype for just about any possible human situation, it seems; and conversely each archetype can produce an indefinite number of archetypal images. And apparently we can make up archetypes at will. Is there a solar penis archetype? That seems surprisingly narrow for a fundamental a priori category of the imagination. A few minutes thought can yield a dozen archetypal possibilities, from masculine generativity to magical control of the weather. In the endless list of archetypes, how do we decide?

And if the person who has produced the numinous image gets to decide with which mythic motif or fairy tale situation it most clearly resonates, then it is not clear why we need to postulate transcendental archetypes of the collective unconscious at all.

Psychologist James Hillman faced this issue squarely, and he chose to eliminate the noun archetype altogether, while preserving the adjective archetypal. The problem, he says, is that Jung moved “from a valuation adjective to a thing and invented substantialities called archetypes… Then we are forced to gather literal evidence from cultures the world over and make empirical claims about what is defined to be unspeakable and irrepresentable.”

But we do not need to take the idea of the archetypal in this reified sense. Any image can be archetypal, Hillman says; it need only be given value — archetypalized or capitalized — by the person experiencing it. “By attaching archetypal to an image,” he says, “we ennoble or empower the image with the widest, richest, and deepest possible significance.”

This view informs Hillman’s approach to dreams, which is not hermeneutic, as it is for Jung, but rather phenomenological or, in Hillman’s term, imagistic, image-centered. “To see the archetypal in an image,” he says, “is not a hermeneutic move.” He thus sees little value in traditional amplification. “Hermeneutic amplifications in search of meaning take us elsewhere, across cultures, looking for resemblances which neglect the specifics of the actual image.” Instead of asking how an image is related to an archetype, the patient begins with and concentrates on images in all their multiple implications — a process psychologist Stephen Aizenstat calls animation, “entering the realm of the living dream.” The idea is to personify the image, ask it questions, interrogate its purposes, engage it as a teacher — even identify with it and question its meaning as one’s own. Hermeneutics is replaced by imagination.

By all means, read the entire article over at singingtotheplants.

Hillman’s heresy is mostly on the money for me.

Continue reading

Filed under analytic(al) psychology

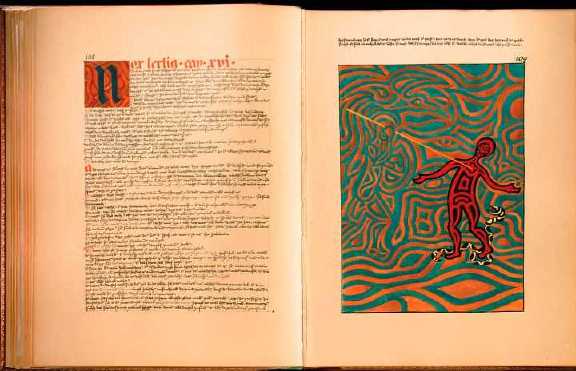

Sara Corbett, writing in the Sunday New York Times Magazines, tells the story of the publication of Carl Jung’s most prominent, heretofore unpublished, work, The Red Book. The Holy Grail of the Unconscious

Seeing the article trumpeted on the magazine’s front page, then slowly taking in photos of several two page layouts, and then, finally, reading the article carefully, made for an unanticipated pleasure on a Sunday afternoon.

Although the story is a good one, here I’ll highlight the author’s summary of part of Dr. Jung’s long (1975-1961) life.

Carl Jung founded the field of analytical psychology and, along with Sigmund Freud, was responsible for popularizing the idea that a person’s interior life merited not just attention but dedicated exploration — a notion that has since propelled tens of millions of people into psychotherapy. Freud, who started as Jung’s mentor and later became his rival, generally viewed the unconscious mind as a warehouse for repressed desires, which could then be codified and pathologized and treated. Jung, over time, came to see the psyche as an inherently more spiritual and fluid place, an ocean that could be fished for enlightenment and healing.

Whether or not he would have wanted it this way, Jung — who regarded himself as a scientist — is today remembered more as a countercultural icon, a proponent of spirituality outside religion and the ultimate champion of dreamers and seekers everywhere, which has earned him both posthumous respect and posthumous ridicule. Jung’s ideas laid the foundation for the widely used Myers-Briggs personality test and influenced the creation of Alcoholics Anonymous. His central tenets — the existence of a collective unconscious and the power of archetypes — have seeped into the larger domain of New Age thinking while remaining more at the fringes of mainstream psychology.

A big man with wire-rimmed glasses, a booming laugh and a penchant for the experimental, Jung was interested in the psychological aspects of séances, of astrology, of witchcraft. He could be jocular and also impatient. He was a dynamic speaker, an empathic listener. He had a famously magnetic appeal with women. Working at Zurich’s Burghölzli psychiatric hospital, Jung listened intently to the ravings of schizophrenics, believing they held clues to both personal and universal truths. At home, in his spare time, he pored over Dante, Goethe, Swedenborg and Nietzsche. He began to study mythology and world cultures, applying what he learned to the live feed from the unconscious — claiming that dreams offered a rich and symbolic narrative coming from the depths of the psyche. Somewhere along the way, he started to view the human soul — not just the mind and the body — as requiring specific care and development, an idea that pushed him into a province long occupied by poets and priests but not so much by medical doctors and empirical scientists.

That’s a fairly good recap.

“Venus” figurine. Est. 35,000 years old.

I’m looking forward to receiving another visitation from Dr. Jung.

Continue reading

Filed under analytic(al) psychology

“It is not the incarnate Sophia’s role to bind or connect us to the earth, but to help us recognize that our understanding of ourselves as separate from the earth is a delusion.” Henri Corbin

discovered in the article, SOPHIA AND SUSTAINABILITY; Bernice H. Hill; CG Jung Page

Ms. Hill writes in the closing paragraph,

Our way through the present environmental crisis requires that we mature; that we free ourselves from too local, too self-serving a perspective; that we move beyond our fear of life’s cycles to become “citizens of the world.”

This dovetails much with my own reflections about how to conceive of larger human systems which I would pose as ‘parents’ to the ‘child’ systems given by perspectival framings of sustainability.

Filed under Uncategorized

These are all scattered excerpts from Jung’s book “The Undiscovered Self: The Dilemma of the Individual In Modern Soceity.” Jung rarely talked about politics in his work. In fact I’m quite sure this was the only time he did, only in reference to his individualism (so for those of you looking for a book centered around politics, this isn’t it). DevilsAdvocate55 (YouTube)

Actually in the collection of essays, Jung Speaks, Dr. Jung is much of the time concerned in various ways with the problem of current events, unconsciousness and group psychology, thus with politics. Similar writings are found in other collections. Then, taking the analytic and main psychologically focused works in total, n those volumes often the problems of the personality are set against the problems of collective psychology, so their import may also be ramified in politics.

Filed under analytic(al) psychology, folk psychology

“Heart of Jung”…carry over from the old Hoon web site to the new Tools for Transformation blog.

I say: ‘Fulfill something you are able to fulfill rather than run after what you will never achieve. We can modestly strive to fulfill ourselves and be as complete human beings as possible, and that will give us trouble enough.”Carl Jung

Filed under analytic(al) psychology

In ancient Greece, the masculine was trying to find consciousness and the hero was the great myth. It summoned great power — even into the first world war. The more matter you had, the more power you had — the more you were the great hero. The massacre that happened at Vimy Ridge and other places really made people question the great hero myth. And certainly the second world war brought it home even more. And Vietnam really ended it.

As I see it, patriarchy became a power principle. It really has very little to do with masculinity. The genuine creative masculine was massacred by patriarchy just as much as femininity was.

The virgin, as I use the word, is the initiated virgin — the feminine of men and women that has worked very hard to find her own values. She is able to sound into her musculature — this is my emotion right now, these are my values. I speak from my heart, my gut, and this is who I am. And she is sexually alive.

This femininity brings men, women and children into their bodies so they experience life. The sacredness of the body is the container that opens to spirit.

The consciousness I am talking about has never been on earth before.

Excerpted from an interview by Alice Klein with Jungian analyst, Marion Woodman

Filed under psychology

My own sense is that C.G.Jung’s lifework becomes mostly phenomenological and echoes his Jamesian roots profoundly in its last stage, when his alchemical inquiry moves into peculiarities of soul-making unable to be encompassed by a dualistic psychology of complex and transference. (It is in this last stage that Jung’s psychology truly becomes paradoxical and justifies the essence of ‘irrational facts’.) This crossover finds a place in the post-Jungian universe firstly through James Hillman.

Filed under analytic(al) psychology