“I think that is the ultimate insensitivity, anyone looking at that with any common sense would say, ‘What in the world would we be doing, you know, fostering some type of system that allows this to happen.’ Everybody knows America’s built on the rights of free expression, the rights to practice your faith, but come on.”

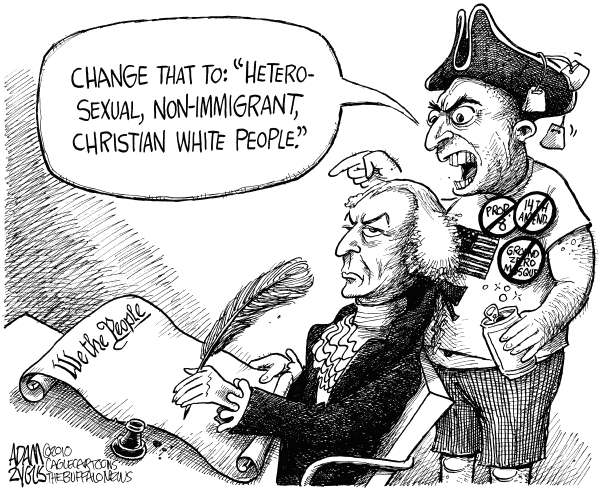

Eric Cantor, R-Va, said this recently. This is my favorite bald, asshat quote of the year–so far. It’s palinesque in its appeal to (some version of) commonsense, and it’s not at all over-the-top, given the waves of grotesque rhetoric the Cordoba House project has evoked. Cantor’s opinion here doesn’t amuse me because it is of the tinfoil type. (There’s plenty of that of course, much of it subsisting on the belief President Obama is a Manchurian candidate and, maybe, the world’s most un-Muslim-like Muslim.) No, what I enjoy about this quote is how it encapsulates the falling away of a whole string of conservative pieties: First Amendment, for suckers; Local governance-fuhgetaboutit; God-centeredness-who needs it?While, out of nowhere, Cantor here seems to embrace political correctness–got to have it, and got to have it rotate around being sensitive.

This last play in favor of sensitivity captures, evidently, a new Republican move to embrace sensitivity! Who would have thunk it? But, sure, “being sensitive” should probably trump the Constitution if one is willing to flip flop on what used to be a longstanding, thorough-going principle of personal responsibility. (I chose this one, from among several delicious choices.) Isn’t the ideologically driven advice from Republicans almost always along the lines of: ‘suck it up!’ ‘take care of yourself’ ‘obey the Constitution and our Christian foundations’ etc.? Until now.

Another impressive feature of the Republican embrace of, this time, religious bigotry, is how sanctimonious Cantor, Gingrich, Palin, are about the composition of necessary exceptions to the First Amendment. So: ‘We’re tolerant, we’re pro-Constitution, but, let’s face it.’ I had thought the Constitution was more hallowed than the site of the 9-11 attack.

I’m sure I’ll know it when it happens: when any of these self-identified bright lights attach an argument favorable to the First Amendment to their politically-correct call for sensitivity about the sensitivities of religious bigots and their reactions to a project that has zero to do with Jihadi aspirations.

Meanwhile, Jeff Merkley, D-OR, framed the ‘cognitive’ issue, and other facts, succinctly:

“I appreciate the depth of emotions at play, but respectfully suggest that the presence of a mosque is only inappropriate near ground zero if we unfairly associate Muslim Americans with the atrocities of the foreign al-Qaida terrorists who attacked our nation. Such an association is a profound error. Muslim Americans are our fellow citizens, not our enemies. Muslim Americans were among the victims who died at the World Trade Center in the 9/11 attacks. Muslim American first responders risked their lives to save their fellow citizens that day. Many of our Muslim neighbors, including thousands of Oregon citizens, serve our country in war zones abroad and our communities at home with dedication and distinction.”

These facts of the matter go in one hand and the clear imperative of the 1st Amendment go in the other hand. Yet, this doesn’t settle the matter in a lot of people’s minds. Why this is so is of great interest to me. Opposition to the Cordoba project’s site location is not singular at all. It’s not simply only due to ignorance, or only due to practiced agendas, or only due to some politicized version of common sense.

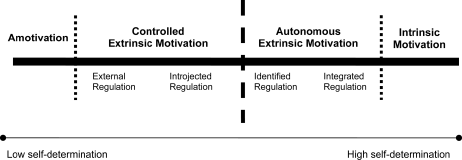

Opponents’ antipathy surely can be understood in terms of psychology, yet, at the same time, understanding the nature of internalized distrust, false attribution, and, confirmation bias–to pick one constellation of behavioral features–doesn’t completely resolve that which constitutes behavioral explanations for upwelling of fear, anger, and, strong dislike, (ie.antipathy.)

The opposition is wide spread and encompasses a wide variety of people, and this surely includes persons who are highly educated, well-traveled, and, intelligent. The group of opponents also would have to include the opposite of this characterization, and, as well, include persons who believe all religions except for their own are members of a satanic opposition.

No simple explanation covers the entire group. But, Cantor’s prescriptive “come on” is simple. And, from this, it is apparent that a system of laws stands against very intense socially affective constructions. From my perspective, none of this yields to just supposing strong feelings based in counterfactual, socially-reinforced interpretations explains the, for example, commonsensical appeal to sensitivity, and fright about the strict ramifications of the 1st Amendment. Although, antipathy certainly isn’t, nor could it be, linked to opponents working through the salient facts. Those facts are also: simple.

But, the intense upwelling of affect, posed as it is by Cantor to literally trump the 1st Amendment, stands with all sorts of other propositions; propositions held by large groups of people with enthusiasm. Such enthusiasms do earn an account at least for reasons having to do with collective aspirations, which if realized, would subvert, if not overturn, all sorts of protective, often lawful, norms.

What and why and how people come to believe stuff has been one of the handful of my central interests for almost forty years. There is nothing surprising about the range of beliefs found at the extreme end of the continuum of antipathy about Muslims, and, similarly, about gays, Darwin, Democrats, elites, capitalists, banks and bankers, Dick Cheney, on and on.

In noting this, generally, it is optimal for people to internalize and be able to cope with factual, thus realistic, fears, sorrows and anger. Nevertheless, (I suggest,) a lot of energy and instinctual (or primary,) process potential attends to the status of our closely held beliefs–in the context of our each apprehending our various realistic and unrealistic interpretations of that which threatens those same beliefs. Antipathy may generally express primal fears oriented to not only having an Islamic cultural center set two blocks from where 9-11 unfolded, but also oriented to the very ideas that other believers, be they Muslims, metrosexuals, Harvard grads, Mexican laborers, progressive Democrats, (etc.,) have set themselves a bit too close to the home of belief–the self; and too close to: me and my own.

For me this antipathy spirals around the ‘low ordering’ of belief; about which I will riff in an ensuing post.